Welcome back. My name is Artie and I’ll be your teacher today.

[But you can be my teacher, please. To do so, please suggest edits to the following chapter of Why People Do, the barely awaited new marketing textbook for mortals. I’d be happy for any suggestions, including identification of proofreading errors.]

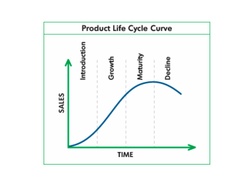

Today: The Product Life Cycle

O, delicious curve. I love every gentle rounded smoothness of you. Mmmm.

More than a sensual delight, the Product Life Cycle Curve is a dear friend to all who want to better understand the challenges and alternatives at hand.

What are our challenges and alternatives? To approach the answer, let us understand more. Let us understand what the curve teaches us.

What Is This Curve?

I do not know the scientific or mathematical name of the curve. (If you do, please tell me. It’s high time I learn her name. For now, I’m guessing: “a Sigmoid or Gompertz function, with a decline or rebirth at the end.”

But, really, what’s in a name? Plenty. Juliet said, “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet” — just remember what happened to her.

- The vertical axis on the left indicates consumer acceptance. At the bottom, revenues are zero. As it rises, revenues are higher. Up is good.

- The horizontal axis on the bottom indicates the passing of time. From the distant past on the left to the far-off future on the right — time marches on.

- The cycle has, in this drawing, four phases: introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. Each represents a moment in time for our product.

The question is: what time is it for our product right now?

Well, I dunno. What time could it be?

Are We In Introduction?

How would you know that your product is in the introduction phase of life?

First, sales are low. But that’s not the only factor in determining whether we are in introduction. Sales might be low because the product stinks. So there must be more.

A product is in the introduction phase when:

- It has just revealed some technical superiority. It has a certain quality that no other product claims. Example: UltraWheels were the first major in-line roller skate (quickly outpaced by the RollerBlades brand).

- Adventurous consumers are buying the product. While sales are still low, fans of calculus will note that the line is accelerating, the curve is turning upward at an increasing rate. Who cares? You do. Why? Because this means that sales are actually picking up steam.

- Combining 1 and 2, these adventurous consumers are buying because of the technical superiority. “Technical superiority” is a phrase that is dear to the marketer. We want to have some new fabulous feature in which consumers perceive benefit.

These adventurous consumers are called early adopters. You are an early adopter when you

are the first person on the block to sport some crazy new device — and you find yourself justifying your weirdness by describing some technical superiority that the product offers. Like, “This cologne might smell strong, but really it’s called musk and it attracts the ladies. Just watch.” (Don’t watch.)

Or, “This phone doesn’t work but the interface is delicious so I paid twice as much yesterday as it costs today.”

Or: “It tastes like hell, but it has fiber which makes my bowel movements firm and rich.” Please, early adopter, spare me.

Product Introduction:

An Example from the Middle Ages

[Disclaimer: Allow me to start this story by admitting I don’t know which parts are true. Facts such as names of people, dates, nations and translations into Middle English might be inaccurate. More than “might be,” actually. I downright made them up. Forgive me. May the meaning of the story still be helpful to you.]

In 1327, just after 1:15 p.m. GMT, Bronwith Wiglaf returned to his native England after an import-export trip (and tax-deductible vacation) to Italy.

Among his Italian imports were a carton of forks. This might sound dull to you, Modern Human, but these were the very first forks ever seen in England. Until that moment, the English used only knives and spoons. (And napkins, of course. The English are very, very British.)

“Oh, for goodness sake,” said Mr. Wiglaf’s English neighbors. “Whatever is that thange?”

“This is the forke,” explained Wiglaf. “Each person should have one at mealtime.”

“But, Wiglaf, you moron, we already have a spoone in one hand and knife in the other hand,” cried his neighbors with derisive laughter. “How do you expect us to hold the forke? With our feete? Har, har, har.”

“My friends,” said Wiglaf, holding his hand up to calm them. “This forke is all the rage in Italy.”

“Oy, vay iz mir,” cried his neighbors using a Middle English expression meaning, more or less, you gotta be kiddin’ me. “Enough with the Italians. They’re always inventing new frivolities.”“Be still, my goode neighbors. Don’t get all Anglo-Saxon on me,” begged Wiglaf. “Let me show you how the forke works. You will find it has technical superiority over the spoone and knife. It picks up food chunks nicely.” He demonstrated by spearing a cube of

potato in his shepherd’s pie and lifting the potato for all to see.You know what happened next. They discussed the design of the forke, how it has tines rather than a bowl or sharp edge. They recognized that Wiglaf was an early adopter and they focused on the technical superiority of this newly introduced product.

Moral of the story: Oh, those forking early adopters.

Of course, the fork had already lived in Italy, where it might have already entered a later stage of life. But:

old technology

+ new audience

= introduction

This is like when you bring hot sauce back from vacation. It’s new to your friends, even though you were just in a community where people eat it on their corn flakes every morning.

Enough introduction. Let’s take a look at your growth.

Are We In Growth?

How would you know that your product is in the growth phase of life?

As we move toward the right, into the growth phase, the line flattens. It is rising at its steepest rate, so revenues are continuing to increase. Business is robust. Life is good.

As we move toward the right, into the growth phase, the line flattens. It is rising at its steepest rate, so revenues are continuing to increase. Business is robust. Life is good.

What are the operational challenges? Well, we have to manufacture more product, get the merchandise to the stores, keep the shelves stocked, and let consumers know where they can get more. And we have to keep track of all the money.

But, from a marketing point of view, what is driving consumer behavior?

Here’s what: herd mentality. Like a herd of buffalo, we are all running together. We want to buy what everyone else is buying. We want to join the crowd, get on the bandwagon, and not be left behind.

What this means is that consumers are no longer captivated by technical superiority.

Product Growth:

An Example from the Disco Age

There was a time when I wore roller skates to Central Park to join my fellow New Yorkers in a predictably spontaneous disco dance.

(Actually, I was too shy — and uncertain on skates — with little talent for dancing — so I didn’t ever break into the circle of dancing skaters. But I did watch from the sidelines in my skates. And I encourage you to have the false picture of me disco-skating among the Hot People.)

One day in the early 1980s a skater arrived wearing UltraWheels, which was the first modern brand of in-line skates. (The original patents for inline skates were filed in the 1930s. Here’s an advertisement for them in a 1948 issue of Popular Mechanics.)

When asked about his unusual skates, he responded like Wiglaf. “They are more like ice skates, better for street hockey. They are faster, too.” His answer was all about technical superiority, so we knew this was a case of product introduction. (Since the product was, in fact, decades old, this was a case of re-introduction, but more on that later.)

Within months, however, the park was full of inline skaters. (The disco crowd continues to strap on parallel skates for better dancing.) But by the end of the summer, most non-dancing skaters were sporting UltraWheels and Roller Blades.

And no technical justification was necessary. Once so many folks were buying inline skates, it would be strange to even ask, “Why?”

The answer was self-evident. “Look around, Old Disco Dude. Everyone is loving inline skates.”

That’s the growth phase. Revenues continue because the mass market is buying. No longer are we relying on the courage of a few early adopters.

So, in growth, is worry a thing of the past? Sorry, but no. Worry remains a thing of today. Here are your worries:

- Competitors will notice your success and attempt to make you share the market. (So, that’s why we call it “market share”?) While it might have taken you decades to develop your product idea, competitors will reverse engineer your product and bring a product that is no better, but comes in a different color or lower price. The bastards.

- Early adopters will not longer feel special. I remember, for example, the first person to wear black clothing. It looked strange, but she told us that it flattered her physique (technical superiority). Then, of course, suddenly it seemed that everyone was dressed for the Cat Burglars Cotillion. And your original friend had started letting her bra strap hang out, which is the new black.

- You will get lazy. Counting money all day (I’m told) serves as a lullaby. (Sweet little money, don’t you cry.) You need your energy to prevent the next phase from announcing your impending death.

- You will be the IBM PC and Apple will finally, 20 years later, figure out how to beat you to death. IBM’s PC, like its Windows-based grandchildren today, have always lived in the growth phase, because — as the legend goes — “No one ever got fired buying IBM.” And Apple has always lived in the introduction phase, because only the leading-edge early adopters bought it. In recent years, with its iPod, Apple finally broke into growth. In a big way.

Why not look at that next phase now, shall we? Why, we shall!

Are We In Maturity?

How would you know that your product is in the maturity phase of life?

Sales growth is slowing. Maybe it’s flat. That means, last year’s sales are the same as this year’s. No growth.

That’s it. No example is necessary. You already understand. Bummer.

Still…

Product Maturity:

An Example from the Pantry

I’m not much of a baker. I’ve tried a few times, but I must

not be following the recipe closely enough. I take chances. And I am

rewarded with bread that looks great but tastes like wallboard.So 99% of my career baking has been Toll House Cookies.

Now let us consider the humble box of Arm & Hammer baking soda.

What three questions do we ask about a product when we first encounter it? Remember?

The first question is: What is it? I’m no scientist, but baking soda is sodium bicarbonate or sodium hydrogen carbonate. Between you and me, we can agree: baking soda is rocks in a box. There’s nothing special about it, really.

The second question: Who is the target audience? As far as I can tell, baking soda is for people making Toll House Cookies. At least, that’s how it was 15 years ago. Let’s pretend it’s still 1993. (Don’t tell me you weren’t born yet. If I want to feel old, I can look around my dinner table.)

The third question: What is the product category? Well, there are no competitors for baking soda as an ingredient for my Toll House Cookies. I can accept no substitute and I don’t think any company is goofy enough to try to compete with Arm & Hammer’s ability to put rocks in a box.

But here’s the problem that we learn from the Product Life Cycle. When Artie Isaac, baker, buys his box of baking soda, he has bought a lifetime’s supply. Even if he lives to his goal (96 years old in 2056), that first box will still be one-third full. So sales are flat. Or worse.

More, soon, on baking soda — and how the Arm & Hammer people have figured out how not to live in the flatland of maturity.

But first, a glimpse at the obvious.

Are We In Decline?

How would you know that your product is in the decline phase of life?

If you have to ask, you’re probably in it. Sales are declining. Polish that resume.

Or, while polishing the resume, call me.

There might be time. But time for what?

Time for Messing With

The Product Life Cycle Curve:

Re-Birth

Allow me to add a little line to the top of the curve.

See it? A little tail that goes up when the decline phase would otherwise droop?

I prefer my curve to have this little upward curve segment on it. It’s a clone of the curve segment in the introduction phase.

I prefer my curve to have this little upward curve segment on it. It’s a clone of the curve segment in the introduction phase.

And it is every bit like the curve segment in the introduction phase. It is a challenge to the marketer to find and lever a new technical superiority.

Now, back to baking soda.

So the baking soda people discovered that baking soda takes the bad smells out of the refrigerator. That’s good. If you go to the Arm & Hammer website, the baking soda spokesperson (“Jill”) will tell you how her cheesecake no longer tastes like last night’s fish, because she has an open box of baking soda in what was formerly a funky fridge.

Does it work?

Not so fast. Does it really?

How the heck would I know? Arm & Hammer claims it works, so I guess I believe it does.

But I don’t really know. I’m not allowed to get in the refrigerator and see for myself. And neither are you. So we really don’t know.

But Jill says that my cheesecake tastes less fishy, so I’m inclined to believe her.

And, lo, a technical superiority is born. Arm & Hammer didn’t have to change the product. They just said, put it in your refrigerator and it will do nicely for you. It’s technical. Believe us.

Then time passed and what happened? Again, maturity.

Now, I’ve got my box of baking soda in the pantry and my box of baking soda in the fridge.

What do I have?

Two boxes of baking soda. A lifetime’s supply. And my inertia drags Arm & Hammer back into maturity. Sure, they climbed the curve again to record sales. But they’re back at maturity, with the higher sales no longer breaking records.

So what did they do?

They told me that baking soda can’t absorb those bad odors forever. It must be replaced. When? Every three months.

Is that true? Stop asking me. I don’t know.

But they put a little place for me to write my own expiration date on the carton. So I’m constantly reminded that the stuff might not be working.And, perhaps through the miracle of suggestion, my cheesecake starts to bear a hint of halibut.

So I open a new box and place it in the refrigerator. But what do I do with the old one?

“No problem,” says Arm & Hammer. “Wash it down the drain with running water.” And this gem: “It will make your drain smell sweeter.”

Now, I don’t know about you, but I never before cared much what the drain smells like. In fact, I keep my nose away from drains. If I smell the drain from across the room, I have a plumbing problem.

But, really, who ever cared that one’s drain smell sweet? I mean, drains are supposed to smell off; that’s where the crap goes.

Then Arm & Hammer suggested that a slightly sour drain is just not right, and suddenly we have another way to feel self-conscious.

I imagine coming home from work, greeted at the door by my beloved. I ask gently, “What have you done all day, honey bun?”

She beams and quickly leads me to the kitchen where she says, “Sniff my drain, dear.”

So now we care. And Arm & Hammer has hogdupled its sales to me. One box once lasted a lifetime. Now I am, at a minimum, pouring a box down the drain every three months.

And, if you visit their website, you will see that baking soda can do all sorts of cleaning in your home and life.

Though they doesn’t suggest it, once I visited the website, I planned to wake up the next morning and roll out of bed, onto the floor rolling in the stuff — to clean myself, the carpet and (if we had one) our dog.

Born Again

So that little line, the upward spur on the top of the Product Life Cycle Curve, is the curve starting over.

With Arm & Hammer, the new line represents them levering their rocks by putting them in bigger boxes (laundry detergent), bottles (liquid detergent), other boxes (cat litter and litter deodorant), tubes (toothpaste), and anything else they can imagine. Walk through Target looking for the Arm & Hammer logo. You’ll see it everywhere.

Can you think of another use for baking soda? You can be sure that there are marketing experts at Arm & Hammer right now struggling to come up with a new use.

Because, as each new product creates new consumer demand, the curve regenerates and new revenue opportunities are found.

That concludes my formal presentation.

Special thanks to Holly Bell for her proofreading. Do you have any editing suggestions? Please do contact me.

A shorter URL for this page is http://tinyurl.com/CCADmarketing2.