Don’t ask what the world needs, ask what makes you come alive, because what the world needs is more people who have come alive.

Don’t ask what the world needs, ask what makes you come alive, because what the world needs is more people who have come alive.

— Howard Thurman 1899-1981

Roger Tory Peterson — to the land and sky what Jacques Cousteau was below the sea — taught that one need not go far to study nature. Just outside. As a child and then as a world-renowned naturalist, Peterson would pick a place outside and look at a single square foot. What’s on the ground, what’s in the growth — just in that square foot — and looking up, into a square column defined by that square foot: what’s buzzing low or flying high overhead? Study that square foot (and up) and make a quiet inventory of its contents.

That’s enough nature to study for this moment. Enough nature to study, perhaps, for a lifetime?

A Single Rock Nearby

So here I sit, at Bright Angel Creek, beside the creek — and a little in it, as I dip my feet and ankles in the fast running, icy water — observing the life of a single rock, a few feet upstream. It’s an irregular shape (rocks’ll be that way), but it is roughly a square Peterson foot. The top of the rock is dry, showing a variety of veins of colors — all shades of sienna — and reminding me of the larger landscape here in the depths of the Grand Canyon’s geologic striations.

We are at the bottom of the Earth, among prehistoric growth. The sudden appearance of clade Dinosauria would seem fitting.

I found my way to this rock after lunch, when Alisa said at our picnic table, “You know what would be good for our sore legs and feet? Getting them into that cold water.” Then she went off to take a nap in the hot tent — finally dry from a very dewy night of in-tents rain. It didn’t rain intensely; it rained in our tents (from our own breath, I suppose).

Which reminds me and probably you, if you are 12 or older, of the old joke:

A man calls his Vistage chair in a panic, shouting, “I’m a wigwam. I’m a teepee. I’m a wigwam. I’m a teepee.”

“Whoa, whoa,” says the chair. “You’re two tents.”

But you didn’t ask for that.

You asked me to tell you something about this trip. I’ve been mentioning it and preparing for it and dreaming about it ever since I was last beside this creek — and the time before that, this being my third time here — so you might have inquired about the trip.

Thanks for asking. It’s a big trip.

Not For These Three

I get the idea that it wasn’t a big trip for the three creatures on this nearby rock. As I watch this square foot of stone, there is a dragonfly, a common house fly — though I can’t imagine this fly ever living in a “house” when she has the Grand Canyon as a home — and some third little thingy, something so small he looks like he could be plant matter, bobbing along the unpredictable waters edge, splashing constantly on the downcreek side of the rock, a place where this third creature specializes in his craft of staying alive.

Staying Alive Is Job #1

That’s pretty much what all of us are doing in this beautiful, rugged terrain, each of us in our own ways.

There are 180 or so folks visiting down here, plus National Park Service Rangers and concessions staff and a nearby construction crew who are replacing a segment of the Transcanyon Water System. In our party: Alisa and me, Helen, and Helen’s (and our) friend from NYU and, now, its afterlife, Micah. The kids are staying alive very nicely: off with their sack lunches walking a moderately strenuous path for great views along the way and at its terminus over the Colorado River. Alisa is staying alive in the open tent, napping and catching the heat of the day.

I am staying alive, nursing my tired feet and sore ankles in the icy stream. Yesterday we descended. We ache.

It’s in the high sixties, I reckon, down here on the Canyon Floor, the bottom of the Inner Gorge. The canyon floor has the weather of Phoenix; the Rim, Flagstaff.

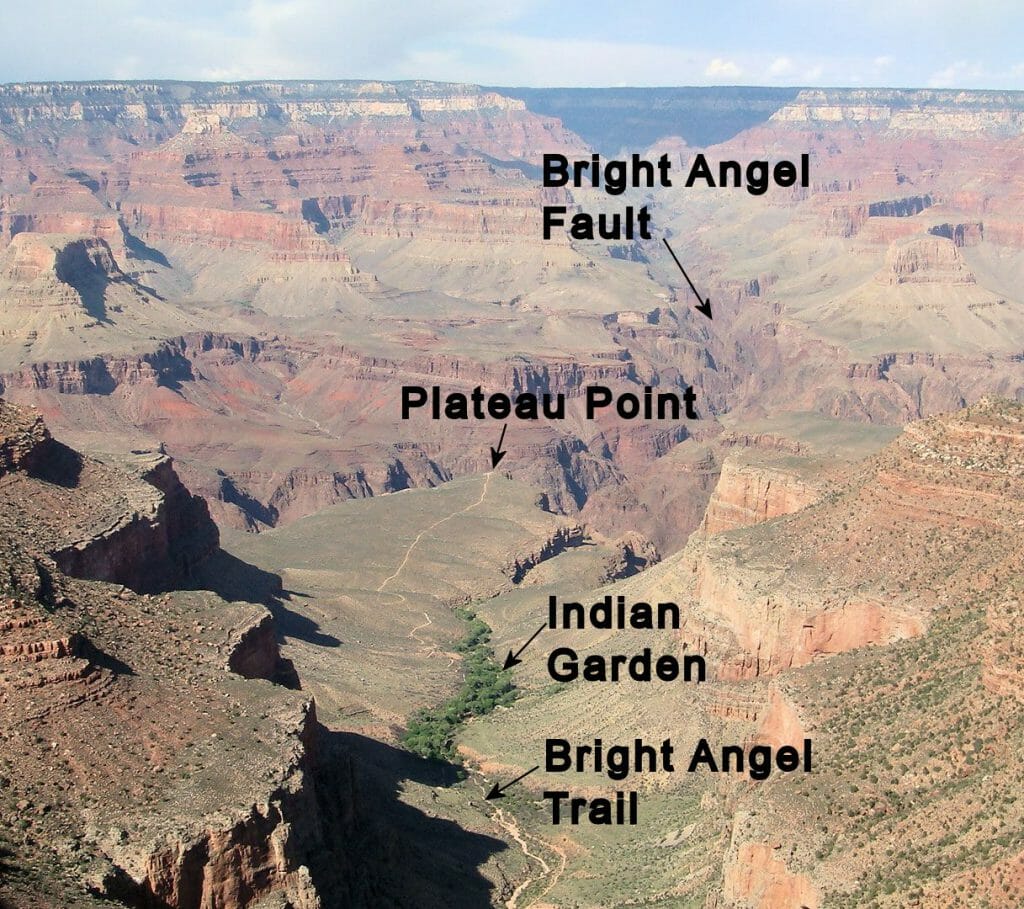

Our itinerary was to leave tomorrow with the majority of our gear (most of which was delivered to nearby Phantom Ranch by mule train yesterday) and set up our tents at Indian Garden, on the Tonto Plateau, the bottom of several of the Upper Gorges, about half way up Bright Angel Trail, finishing the walk the next day.

Suddenly: Snow!

But — hard as it is to imagine — snow is forecast for above 5,000 feet, starting at Indian Garden. After last night’s shivering sleep (hard to remember in the desert sun) and what is probably more of the same tonight, we know we aren’t outfitted for higher elevation camping.

Still, everything is a delight.

Overnight, Alisa and I, independently — and perhaps the kids — I don’t know — took turns shivering ourselves awake to silently wonder how to convince the others that we were simply not going to camp in the November cold of Indian Garden. At breakfast all were agreed, with Micah abstaining — “whatever you guys want to do, I’m up for it.” We’ll stay another night down here, and head all the way up tomorrow.

Meanwhile, back beside the stone, I dip my feet and ankles into the rush of the water. Moments ago, I could put my foot in for 5 seconds, before it was numbed. Now I can permit only a momentary dip and right-up-and-out again, and even then, my ankles feel painfully numbed. I wonder how athletes survive those therapeutic ice baths in the training rooms.

A Roger Tory Peterson Nature Drama

The dragonfly sits atop the rock. His pencil-lead body points downstream. He’s waiting for something important, or perhaps just enjoying the mottled sunlight, dropping through the creek’s canopy, like I am. When undisturbed, he just sits.

The housefly disturbs. Moving around the stone, every once in a while the housefly clumsily bonks into the dragonfly. Two flies, face to face, the coming together of two sets of compound eyes must appear as a crash of civilizations. How can the housefly be so careless?

They both act surprised: each jetting off into the air with evasive maneuvers. The previously all-black dragonfly reveals blood red inner wings.

Immediately, the non-threat resolved, both resume their posts: the dragonfly facing downstream, the fly moving about, showing no interest in rest.

The third creature has blown or swum out of view, finding — or being — lunch.

A few other houseflies alight, but Our Housefly protects the habitat and they are exiled to some other rock.

Phantom Ranch

The crew here at Phantom Ranch are dear and hospitable. We take our meals here — full breakfast, served family style, a sack lunch, and a dinner, also family style. One server provides 40 meals all at once. The grateful diners collaborate, passing the food around the table.

At breakfast, we decided to advance the itinerary: up and out tomorrow, without pausing overnight at Indian Garden. After a phone call from the Ranch to El Tovar, we secured rooms and dinner reservations for the earlier night. And we canceled our original night’s accommodations.

We don’t want to stay two more nights on the Rim. Being in the Canyon, sleeping below the Rim, ruins you for the South Rim experience: people taking photographs, saying “wow” but seeing only the single, classic macro-wow of the grand brown and red sweep of the horizon. What they miss are the countless micro-wows of a Canyon that becomes lush with the descent, the tumult of life and creatures. The dark of the night sky, a carpet of stars. The deer that graze within feet, not startled, unconcerned by your presence. The three living things on this rock.

Below the first couple miles of trail — the South Kaibab Trail (the usual descent) is seven miles long to drop one mile in elevation; Bright Angel Trail (the usual ascent, with water) is eight miles long — the humans become more fit and able. A million people peer over the Rim; only 1% make it to the bottom, to the bank of the Colorado River.

Here’s a story about how hard it is…

My Brother-In-Law Joe is a One-Percenter

Five years ago, during my second trip to the bottom, my brother-in-law Joe made the walk to Phantom Ranch.

About half-way down the South Kaibab Trail is the “Tip Off.” This is where a hiker feels like the canyon has been nadired (the opposite of summited?), only to discover that the upper canyon has been nadired and the inner canyon hiking starts there.

It’s a fine place to rest and eat and use the composting restrooms. Mule trains pause here for the mules and their fares.

Then Joe Disappeared

On that 2010 hike, at the Tip Off, Joe was gone a long time. Where’s Joe? He’s known to take his walks, he’s an old hand at desert hiking and beach combing — but he was gone a memorably long time.

Finally, Joe returned and we continued our hike down. Ate dinner and breakfast at Phantom Ranch — and hiked up.

Like all of us, Joe trained and prepared and worried about whether or not he was young enough, light enough, physically fit enough to complete the hike. Though some lost weight for the trip, because it doesn’t make sense to carry yesterday’s doughnut to the bottom, none of us was as light — or young, or physically fit — as our knees would prefer.

Anyway, the next night we had summited and were enjoying a celebratory dinner at Bright Angel Lodge on the Rim. After a toast, I asked, “Joe, where the heck were you at the Tip Off yesterday?”

“Oh, yes,” started Joe. “I needed some time alone to decide whether to turn back or keep going. When I saw the Inner Gorge at the Tip Off, I thought that I might not be able to do it, to get down there and then, today, all the way up. I worried that I might die. So, I considered turning back. After thinking about it, I decided to keep on going down.”

This made me curious. “Joe, I understand turning back. I understand fearing for your life, and demonstrating discretion and returning to the Rim. I understand that. What I don’t understand is going further down.” I asked, “What were you thinking at the Tip Off?”

“I thought long and hard,” said Joe, “And, off on my own at the Tip Off, I concluded that I had a steak dinner waiting for me further down at Phantom Ranch.” Everyone laughed. “And, second, I recognized that I have to die somewhere. Dying in the Grand Canyon is as good a place to die as any other.”

Silence. He was serious.

I think most anyone standing on the Canyon floor — anyone who is aware of his or her own mortality — fears the Canyon. It is a mountain climbed in reverse. Going up is twice as hard as it was going down. (Maybe. Going down is hard on the joints. Going up is hard on the muscles, including the heart.)

And, more dramatically: when you are the bottom of the Canyon, the Rim stands before — and above — you as a goal that must be reached for survival. You can’t finish the hike, by falling up the trail. Sure, there is always a $20,000 helicopter ride that can be ordered. But, please, no.

Some Folks Are Meant To Hike

On the main corridor trails (Bright Angel, South and North Kaibab), hikers like us — earnestly outfitted, wary of the challenge — encounter marathon and endurance runners who are running Rim-To-Rim-To-Rim (round trip across the Canyon and back) in a day. It’s a 18-hour experience (I suppose).

In any case, the folks at the bottom of the Canyon are not a general cross section of the American public. They are serious about physical exertion, about nature — and they are older than the youngest Americans and younger than the oldest. And, of course, they aren’t all Americans; they come from all over the world to take this walk. Languages are an aural striation at the dinner table, just like the geologic striation in the walls of the Canyon.

One man passed us — he on the way up, we on the way down — and he was all smiles. He came toward us, loudly saying, “You are awesome! You guys are awesome!” As he passed, he put up his hand for a high five. High five with Alisa. High five with me. “You guys are awesome!”

I loved that moment. I want to be more like him. I want you to know — you who are reading these words — you are awesome! High five!

And The Unfit Are Here.

Sometimes, I have come across hikers who are in over their heads. Some examples:

- A couple struggled on the Bright Angel Trail on this trip. A single step. A pause. A single step. A pause. Stooped low by their packs and their own physical frames. As we passed them, I asked, “Are you OK? Do you want us to carry some of your gear?” “No,” one of them replied. “This is the plan. We are still on plan!” “You make it look easy,” I said. “You are awesome! You guys are awesome!” And we all laughed. They took a single step. Paused.

- On the second trip: A couple were sitting on a rock, three-quarters of the way up Bright Angel Trail, a place that is surely the hardest, as the trail becomes the steepest. He was winded, sitting. We inquired about his well being. “My husband is having trouble,” we were told. We offered to carry some of their gear. “No, thank you.” I worried about them, but was confident that they would get out, though perhaps long after nightfall.

- On the first trip, which was taken (ill advisedly) during July, we came across a woman hiking alone. We were descending South Kaibab — she was ascending — on the upper half of the trail. Hikers greet one another, but she didn’t respond to my hello. She had a distant look in her eyes. She plodded forward, her steps slightly erratic. This was my first hike, so I didn’t quite know what to do. (These days, I would inquire more urgently.) As she passed, I saw that she didn’t have a backpack. I said, “Duncan, did she not have a backpack?” In the scorching sun and heat, every hiker must have a couple liters of water (and a pound of food) to survive. She carried nothing. Duncan agreed: no backpack. And she was gone, up trail. We walked on, ourselves challenged by the intensity of the desert and our increasing fatigue. A quarter-mile down trail, we found it: her backpack, jettisoned on the trail, the birds already dancing around it. If she lived through that day, it was because another, more experienced hiker found her and intervened.

Think me too morbid? Too dramatic?

On our return, I learned that — the same week — a friend had died hiking. Focused as we are on the loss of him — a loving husband, father, brother, son; a generous community volunteer; a talented doctor; a talented musician; so much more — I haven’t heard much about his death. All I’ve heard: “They were on a hike in Patagonia. He said, ‘I don’t feel well.’ And he lay down and died.”

Bob Darwin was a mensch. (His obituary = tinyurl.com/BobDarwin )

At the memorial service, I sat and listened to Bob’s family and best friend describe him in a way that was completely unsurprising, even though I didn’t know him well. Unsurprising: he was a mensch in every moment, at every turn. I believe this. Their praise matched my every interaction with him during the decades. I don’t think these words of praise were shined by the Hyperbole of Mourning.

Bob Darwin lived an exemplary life. He is my role model at home, at work, and beyond. I’ll never match him. I’ll just miss him, standing beside his mourners, wishing I’d known him better.

I feared.

Days before Bob died, I paused on the Bright Angel Trail.

It was in the final ascent, after leaving the Mile And A Half Resthouse, when the air is thinnest and coldest, and the trail climbs the steepest walls of the canyon. (The graphic shows that fearsome truth, the view down from the point where there is still 1.5 mile of trail ascending . If you can’t see it, because you are reading this off-site, visit artie.co.)

It was in the final ascent, after leaving the Mile And A Half Resthouse, when the air is thinnest and coldest, and the trail climbs the steepest walls of the canyon. (The graphic shows that fearsome truth, the view down from the point where there is still 1.5 mile of trail ascending . If you can’t see it, because you are reading this off-site, visit artie.co.)

We had strapped on our crampons, slip-on shoe traction devices, like snow chains for your feet, because there was ice, mud, and icy mud on the trail.

I felt winded. I was nauseated. I was faintly faint. Alisa was responsibly eager to summit, to get to warmth, put down her bag, and put up her feet. I told her, “Go on ahead. I need to rest.” I didn’t describe my symptoms.

She’s had a lifetime of drama from me, so she thought (she later told me) that I wanted to pause for the view.

Yes and.

Yes, I wanted to pause for the view. But I also thought I truly needed the rest. I was afraid that I might be overdoing it. That I might hurt myself.

She walked on. I took off my coat to let the sweat evaporate. A moment of chill would dry my clothing for the cold walk ahead.

I caught my breath. My stomach settled quickly. I walked on. (Didn’t catch her until the top.)

We didn’t talk about my momentarily mortal fear until a week later, after coming home from Bob’s memorial service. “What are you thinking?” she asked. I told her.

“Oh, my.”

Where Will You Die?

Whenever I climb the Bright Angel Trail, after the Mile And A Half Resthouse, I think I’m going to die. I fear I could die in the Grand Canyon.

Then I don’t. I summit. I didn’t die. I dine.

And, in some reckless dance with Mortality, I decide to book another trip into the Canyon. If it is my destiny to die there, I need to do my part. I need to go back down below the Rim.

Another Joe, Joe Faessler, the legendary Vistage Chair, heard me describe this and said, “This speaks to the grandeur of your life, Artie. Most people die and are placed in a small hole.”

I Can’t Go Back.

I Must Go Back.

This is one of the reasons I’m not a Buddhist. I am fully attached.

Helen asked me, “Why do you keep coming back here? It is beautiful and unique. It is worthy. But there are other beautiful places which are easier to get to. Why do you keep coming back here?”

I do not want to see a place for the last time. It fills me with dread to think, “This is the last time I will be here.” I return to places again and again. At first, it is to confirm what I have seen. Then, it is to learn more about the place, to experience it more deeply. Then, however, it is a match with Mortality. If I am seeing a place for the last time, I am closer to death.

I don’t have a Bucket List. I have seen everything I want to see. I have tasted everything I want to taste. I have kissed everyone I want to kiss. I do not hunger for new. I hunger for familiar.

I want to return to every place — and person — I have ever known.

I do not want to see you for the last time.

Thanks.

-

To Duncan Isaac, my first trail mate on these trails. He and I walked in July 2008. It was so hot that we departed Phantom Ranch at 3 a.m. for the hike up and out. We walked in the nighttime heat and dark for the first several hours. Walking in the dark? You can do that at home! Duncan and I were experienced hikers for the second hike in 2010.

To Duncan Isaac, my first trail mate on these trails. He and I walked in July 2008. It was so hot that we departed Phantom Ranch at 3 a.m. for the hike up and out. We walked in the nighttime heat and dark for the first several hours. Walking in the dark? You can do that at home! Duncan and I were experienced hikers for the second hike in 2010. - To Alisa, Duncan, Helen, Micah, Joe, Dory, and Lily and the 100s of other hikers who have walked with me in the Canyon. Like worship, hiking is less when unshared.

- To Jason Dolin, who introduced me to Edward Abbey’s 1968 classic Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness, a book that shaped National Park Service design strategy (away from accessibility and toward conservation). On this most recent trip, I asked a first-time visitor whether he had ever read the book. “Yes,” he said. “Twenty years ago. And ever since then I have wanted to come here.” I encourage you to read it. I think this is where my desire to hike the Grand Canyon was first hatched.

- To the physical therapists and trainers at Fitness Matters (fm2us.com) — Travis, Jamie, Andrew, Kerry — who have expertly and diligently helped Alisa and me prepare to walk the Canyon and the rest of this world.

- Annie Dillard for her Teaching a Stone to Talk: Expeditions and Encounters. In this short volume, Dillard weaves three natural stories: the earliest attempts to reach the North Pole, a solar eclipse, and observing a weasel in the woods. My encounter with the dragonfly, housefly, and third thingy is surely influenced by her book, a long-time favorite of mine. I encourage you to read it.

- To the National Park Service staff and concessioners, to President Theodore Roosevelt, to the State of Arizona, to the State of Utah — and to all taxpayers who share in the ownership of these magnificent natural treasures. For more information on your wealth: www.nps.gov/grca.

On A Rock

Somewhere, right there, in Bright Angel Creek, three creatures share a rock.

The housefly says, “Nothing to be done.” The dragonfly says, “Will the green thingy return again today?” The green thingy returns.

Night is falling on Bright Angel Creek.

Where will the three creatures survive the night? How will they stay alive?

How will I stay alive? I will return to Bright Angel Creek.